We are honored to be the institutional home of this spectacular collection.

Deborah Jakubs

Rita DiGiallonardo Holloway University Librarian and Vice Provost for Library Affairs

The Lisa Unger Baskin Collection: Overview

The Lisa Unger Baskin Collection documents women’s work, broadly conceived, from the mid-fifteenth century to the mid-twentieth century. In Baskin’s own words, “The unifying thread is that women have always been productive and working people and this history essentially has been hidden.” This collection brings women’s contributions across the centuries to light.

Carefully assembled over 45 years by noted bibliophile, activist and collector Lisa Unger Baskin, the collection includes more than 8,600 rare books and thousands of manuscripts, journals, ephemera and artifacts. Among the works are many well-known monuments of women’s history and literature, as well as lesser-known works produced by female scholars, printers, publishers, scientists, artists and political activists. Taken together, they comprise a mosaic of the ways that women have been productive, creative, and socially engaged over more than 500 years.

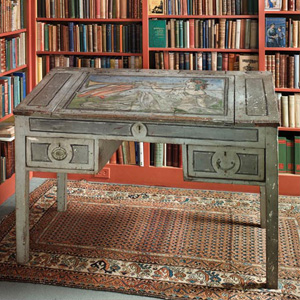

The materials range in date from a 1240 manuscript documenting a respite home for women in Italy to a large collection of letters and manuscripts by the 20th-century anarchist Emma Goldman. The majority of the materials were created between the mid-15th and mid-20th centuries. Other significant items include correspondence by legendary American and English suffragists and abolitionists Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Emmeline Pankhurst and Lucretia Mott; Harriet Beecher Stowe’s publicity blurb for Sojourner Truth’s Narrative, written in Stowe’s own hand; exquisite decorated bindings by the celebrated turn-of-the-century British binders Sarah Prideaux, Katharine Adams, and Sybil Pye; and English writer Virginia Woolf’s writing desk, which she designed herself. A few highlights from the collection are described in this website.

Baskin and her late husband, the artist Leonard Baskin, were both avid book collectors. Leonard also founded The Gehenna Press, one of the preeminent American private presses of the 20th century. Lisa Unger Baskin began collecting materials on women’s history in the 1960s after attending Cornell University. She is a member of the Grolier Club, the oldest American society of bibliophiles.

“I am delighted that my collection will be available to students, scholars and the community at Duke University, a great teaching and research institution,” Baskin said. “Because of Duke’s powerful commitment to the central role of libraries, and digitization in teaching, it is clear to me that my collection will be an integral part of the university in the coming years and long into the future. I trust that this new and exciting life for my books and manuscripts will help to transform and enlarge the notion of what history is about, deeply reflecting my own interests.”

Materials from the collection will be available to researchers once they have been cataloged. Some items will be on display in the renovated Rubenstein Library when it reopens to the public at the end of August 2015.

The Lisa Unger Baskin Collection: Early works to 1700

Lisa Baskin considers the early works in her collection to be its heart. The Lisa Unger Baskin Collection includes critical early landmarks in women’s history as well as extraordinary examples of women’s contributions across a range of disciplines, arts, and crafts.

The Baskin Collection contains Jacopo Philippo Bergomensis’ De Claris Mulieribus (1497), one of the earliest collections of women’s biographies ever published. This work borrows heavily from Boccaccio’s earlier work of the same title. It is one of the finest early Italian illustrated books, and the first to attempt life-like portraits. The final seven woodcuts are portraits of contemporary women, including Catherine of Siena and Margaret Queen of Scotland. The work is monumental in scale, an impressive folio comprising 186 biographies.

Other early works within the collection include two copies of the pseudo Petrarchian text Vite dei Pontefici e Imperatori Romani (1478), one of the first books typeset by women; a beautiful book of hours printed for Louise de Bourbon by Yolande de Bonhomme, Hor[a]e beatissime virginis Marie (1546); and Marguerite de Navarre’s Marguerites de la Marguerite des princesses (1549), a magnificent copy of one of the landmarks of French poetry; written by the first “Modern Woman.”

The collection also contains a letter from Artemisia Gentileschi to Italian scholar and patron of the arts Cassiano dal Pozzo in August 1630. Gentileschi was one of the most accomplished artists of the 17th century and was the first female painter to become a member of the Accademia di Arti del Disegno in Florence. She is perhaps best known for her Judith Slaying Holofernes, now in the Uffizi. The letter concerns her request for a license for her assistant to carry arms and refers to a self-portrait that dal Pozzo had commissioned Gentileschi to paint. This was the only known Gentileschi letter remaining in private hands.

The Lisa Unger Baskin Collection: History of Medicine

The Lisa Unger Baskin Collection traces the evolution of the understanding of women’s reproductive health and documents the contributions of female medical practitioners and professionals.

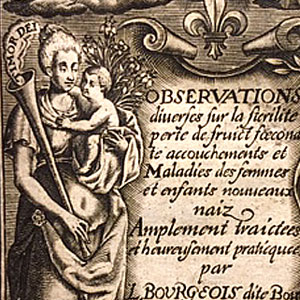

The Baskin Collection includes Observations Diverses, sur la Sterilité, perte de Fruict, Foecondité, Accouchements et Maladies des Femmes, et Enfantes Nouveaux Naiz, (1642) by Louise Bourgeois, the first book on obstetrics to be published by a woman. Bourgeois was an official midwife for the French court for 26 years. Her most famous patient was Marie de Medici. This first collected edition of her lectures was translated into Dutch, German and English, underscoring the breadth of her reputation across Europe. The collection also holds the London, 1663 and Leyden, 1707 editions of this work.

The collection also holds a first edition of Jean Palfyn’s Description Anatomique des Parties de la Femme, qui fervent a la Generation (1708); Nicholas Culpeper’s Compleat and Experienced Midwife (1751), the first book on midwifery in English when it appeared in 1651; William Smellie’s An Abridgement of the Practice of Midwifery (1786), the first illustrated medical book and first book of obstetrics published in the United States; and William Osborne’s Essays on the Practice of Midwifery, in Natural and Difficult Labours (1792).

More recent materials within the collection include Family Limitation (for private circulation, 1914) by Margaret Sanger, who popularized the term birth control, opened the first birth control clinic in the United States, and established organizations that evolved into the Planned Parenthood Federation of America; and Marie Stopes’ Contraception (Birth Control): Its Theory, History and Practice: A Manual For The Medical And Legal Professions (1923). Stopes was a paleobotanist, author, and social activist best known for her efforts in the early half of the 20th century to promote safe birth control for women.

Other notable materials related to the history of medicine include a collection of family papers of Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman to receive an M.D. degree from an American medical school; her sister Emily was the third. The Blackwell family was known for their activism on behalf of women's rights and the Anti-Slavery movement. This significant group of materials dated 1845-1972 includes materials related to Elizabeth Blackwell, Anna Blackwell, Lucy Stone, Alice Stone Blackwell, and Emma Blackwell.

The Lisa Unger Baskin Collection: Suffrage and Anti-Slavery

Lisa Baskin placed an early emphasis on the British and American suffrage and Anti-slavery movements in her collecting, and she has an extraordinary gathering of materials related to the fight for equality. The collection includes important materials related to the leadership of these movements--such as correspondence from Susan B. Anthony, Lucy Stone, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott and Lydia Maria Child--and a significant collection of family papers related to the British Pankhurst and Pethick-Lawrence families. (The Pankhursts and Pethick-Lawrence families provided leadership for the militant suffrage movement in Great Britain). These include the Pethick-Lawrence annotated court depositions for their trial of 1912 and the Pethick-Lawrence pamphlet collection. There are scrapbooks and manuscript journals documenting the Suffrage Pilgrimage of 1913 from Carlisle and Birkenhead to London. Also present are three works bound together that document Stanton’s work to revise Christianity in the name of women’s rights: Bible and Church Degrade Woman (third edition); The Woman’s Bible, Part I (third American edition); and The Woman’s Bible, Part II (first edition.)

Among the rare serials in the collection (including The Una, The Forerunner, The Alpha, Votes for Women, Lucifer, The Free Inquirer, and Mother Earth), Baskin holds the most complete run of Susan B. Anthony’s The Revolution (1868-1872), the first women’s rights weekly journal. Although its circulation never exceeded 3,000, The Revolution’s influence on the national woman’s rights movement was enormous. The paper confronted subjects not discussed in most mainstream publications of the time including sex education, rape, domestic violence, divorce, prostitution and reproductive rights. It was instrumental in attracting working-class women to the movement by devoting columns to concerns such as unionization and discrimination against female workers. Rare pamphlets in the collection include Rev. Alexander Crummell’s Hope for Africa. A Sermon on Behalf of The Ladies’ Negro Education Society (1853). Only four other copies are known.

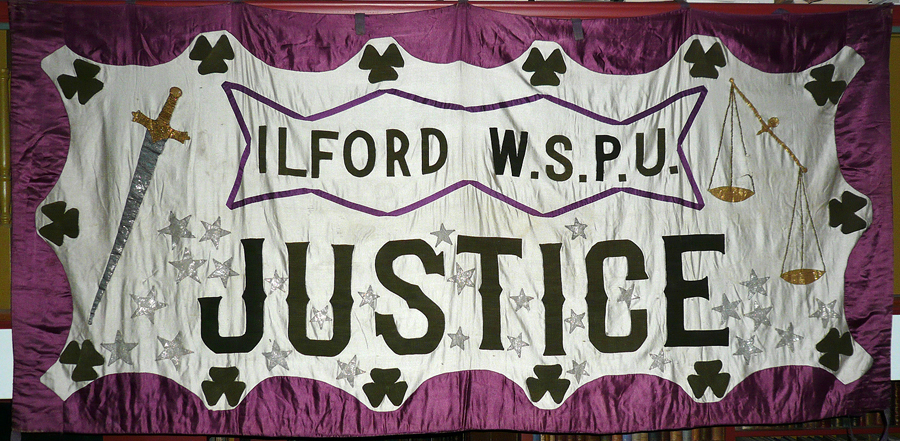

The material culture of the Suffrage and Anti-Slavery movement is documented through a British suffrage tea set (the most complete known of its kind), an Abolitionist dessert service, Anti-Slavery tokens, a very rare large two-sided silk banner reading “Justice” carried in parades by the Ilford (London) Women's Social and Political Union in 1909-1910, several card and board games sold to support the movement, and the preparatory portrait photographs (several signed) used by the sculptor Adelaide Johnson in modeling the sculpture of Stanton, Anthony and Mott (now in the Capitol Rotunda).

The Lisa Unger Baskin Collection: Women Artists

Lisa Baskin’s interest in female artists and their work is wide ranging and includes painters, photographers, illustrators, bookbinders, metalworkers, embroiderers, calligraphers, and graphic designers. The collection holds exquisite, highly decorated bindings by the celebrated turn-of-the-century British binders Sarah Prideaux, Katharine Adams, and Sybil Pye, as well as by the Guild of Women Book Binders. Book historian Marianne Tidcombe has noted that these female binders, working at a time when binding was still more of a trade than an art form, tended to produce more innovative designs than their male counterparts. These examples and others found throughout the collection are an important part of the history of the book as object, typified by Phoebe Anna Traquair’s illuminated manuscript of Tennyson’s In Memoriam, a stunning work by the leading artist of Scotland’s Arts and Crafts Movement, in Traquair’s own binding.

The earliest book in which illustrations by a woman appears is likely to be Antonius Augustinus’ Dialoghi Intorno Alle Medaglie (Rome, 1592). The woodcut illustrations were cut and signed by Geronima Parasole. Her woodcut for the title page is spectacular. The signature she often used combines her initials with a small knife, indicating that she cut the images herself.

The collection also includes correspondence by English artisan, designer and socialist May Morris (the daughter of William Morris, the figurehead of the Arts and Crafts movement.) May Morris became director of the embroidery department for Morris & Company at age 26 and later co-founded the Women’s Guild of Arts. The collection holds an exquisite needlework pouch May Morris made to house a Kelmscott Press edition of Of the Friendship of Amis and Amile, bound by Katherine Adams, which she inscribed for her lover, the American lawyer, John Quinn.

Dutch artist and naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian, who raised the artistic standard of natural history illustration and helped to transform the field of entomology, was the first to observe and depict the process of metamorphosis in the field. During her career, she described and illustrated the life cycles of 186 insect species from direct observation of live insects. The Baskin Collection includes the first folio edition of Merian’s De Europische Insecten (1730) and Erucarum Ortus, Alimentum et Paradoxa Metamorphosis (1718). Both of these copies have hand-colored illustrations.

Baskin has sought out early daguerreotypes and cartes-de-visite taken by women photographers. It is painstaking work to identify these photographers as they are often known only by their first initials, as were many women printers. The bodies of work she has reassembled offer a unique window into the early history of photography and to women’s role in that history.

The Lisa Unger Baskin Collection: Literature

Lisa Baskin has emphasized women’s social history in her collecting, but she did acquire some extraordinary works related to women’s literature. The volumes, manuscripts, and artifacts speak to the work and craft of writing and to the networks and connections between creative women.

Virginia Woolf’s writing desk is one of the most iconic items within the Baskin Collection. Designed by the author herself, the desk is perhaps the most evocative artifact associated with women’s literature, providing a tangible expression of the “room of one’s own” that Woolf so famously invoked in her 1929 essay of the same name. Painted decoration was later added by her nephew Quentin Bell. The Baskin Collection also holds a collection of letters to Aileen Pippett, author of The Moth and the Star, the first full-length biography of Woolf to be published. Her correspondents include Mary McCarthy, Elizabeth Aiken, Conrad Aiken, Vanessa Bell, and many others.

Other materials related to British Literature include a number of items associated with the Brontë family, including a handwritten letter from Charlotte Brontë to her lifelong friend and former schoolmate Ellen Nussey, penned in November 1840. Brontë’s letters to Nussey are intimate and revealing, and have been used extensively by Brontë scholars. The collection also includes a piece of needlework completed by Charlotte Brontë in the early 1830s and a letter from Brontë’s friend and biographer Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell to Ellen Nussey (July 1855) documenting her early steps in writing this first biography of Charlotte Brontë.

Baskin has also acquired some of the most important works of American literature. For example, the collection contains a first edition of The Tenth Muse lately sprung up in America (1650) by Anne Bradstreet, the first female writer in the British North American colonies to be published. It includes a signed first edition of Phillis Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects Religious and Moral (London: for A. Bell, 1773), the first work to be published by an African American. This copy has been mended by hand by an early owner and bears the inscription “Melatiah Bents Book, Milton, [MA,] 1783.” Bents was a widowed tavern keeper at the time she acquired this book, and her inscription indicates how widely Wheatley was known in the late eighteenth century. The collection also contains a first edition of the first biography of Wheatley (B. B. Thatcher, Memoir of Phillis Wheatley, 1834).

Five volumes in the Baskin Collection were previously owned by American novelist Willa Cather. Three of them testify to her close relationship with her mentor Sarah Orne Jewett. The first is a copy of Jewett’s The Country of the Pointed Firs (1894) in a binding designed by Sarah Wyman Whitman. The second, Jewett’s Strangers and Wayfarers, is also in a binding by Whitman and was inscribed by Cather to her partner Edith Lewis in 1908. The third is a copy of Henry James’ The Ambassadors (1903) from Jewett’s library that subsequently became a part of Cather’s library.

The Baskin Collection also includes several significant works by Edith Wharton. Wharton was the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize (for The Age of Innocence, 1920). A typescript in Italian of “La Duchessa in Preghiera” (The Duchess at Prayer) has manuscript corrections in Wharton’s hand. This short story formed part of her 1901 collection Crucial Instances. A limited first edition copy of Twelve Poems (London: Medici Society, 1926) is in its original wrapper and was inscribed by the author “To Trix and Max” (her niece and her niece’s husband). Beatrix Farrand (Trix) was one of the most renowned American landscape architects. Dumbarton Oaks is her finest surviving work. She was the only woman among the eleven founding members of the American Society of Landscape Architects. Max Farrand was the first director of the Huntington Library.

The Lisa Unger Baskin Collection: Other Selected Titles

The highlights presented in this website begin to provide a sense of the depth and breadth of the Lisa Unger Baskin Collection, but the Collection, itself, encompasses far more than these few categories. The thread binding the collection together is the wide variety of ways that women have made a living over the centuries and the importance of their contributions to human progress.

- The Ladies of Llangollen collection. Eleanor Butler (1739-1829) and Sarah Ponsonby (1755-1832), members of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy, determined that they would forego heterosexual marriage and eloped to Northern Wales. Their choice thrust them into the limelight of nineteenth-century press. They were part of a larger culture of ‘romantic friendship’ where other cohabiting women behaved in similar ways. While they lived a life of rural retreat, the Ladies’ relative celebrity and social status attracted many visitors, including poets such as Wordsworth and Byron, and even such luminaries as Queen Charlotte. This large collection includes 380 letters, four poetry manuscripts by Ponsonby, souvenirs sold to visitors, books from their library, and accounts of visits to their home.

- A supportive blurb in manuscript form by Harriett Beecher Stowe of Sojourner Truth’s autobiography (1850). Truth had personally requested that Stowe write the blurb, and she incorporated this text in later editions of the work. Truth sold her autobiography to support herself. The collection also includes a cabinet card of Truth taken in Michigan in 1864, noting “I sell the Shadow to Support the Substance.”

- Florence Nightingale’s Suggestions for Thought to the Searchers After Truth Among the Artizans of England (1860). Though best known as the founder of modern nursing, Nightingale was also at the forefront of religious and philosophical thought. In this very rare three-volume work, Nightingale presents her radical spiritual and feminist views. She also addressed the question of why there are so few women artists. Only six copies were printed for private distribution. This copy was previously owned by Ray Strachey, important feminist historian and author of The Cause: a short history of the women's movement in Great Britain (1928).

- Over 250 unpublished letters and manuscripts by the American anarchist and activist Emma Goldman (1869-1940), including extensive correspondence with Thomas Keell (editor of the journal Freedom) and Alexander Berkman (Goldman’s lover, life-long comrade, and editor of her journal Mother Earth and his journal The Blast) and manuscripts by Goldman and Berkman. Two letters from Eugene V. Debs to W.S. Van Valkenburgh in 1926 discuss Goldman and Berkman's treatment in the Soviet Union. Also present are several letters from Goldman to American anarchist Harry Kelly, a manuscript by the Italian Revolutionary anarchist Errico Malatesta, an anonymous anti-Goldman note written on the back of a flyer for a Goldman appearance in Philadelphia, and a photograph of Goldman at a young age that may be unique

Explore more highlights using the links at right.